by Wine Owners

Posted on 2019-02-18

On 16th February we learned that the magician of Montalcino had died in First floors aged 82.

His style was inimitable, and like all great wines, was capable of achieving an airborne character of great finesse, marrying profound intensity with the utmost delicacy. Many of his greatest wines are marriages of opposites – sweetness and powder-dryness; purity and gaminess; dark aromatics illuminated with the brilliance of crystalline fruit. I’m left wondering at these juxtapositions that make the wines of Soldera so extraordinary.

According to Antonio Galloni in his introduction to an epic Soldera dinner in 2016 held in London at Maze, it was the great Piedmont wines of the 1940s and 1950s that were Gianfranco’s early inspirations.

Soldera bought Case Basse in the early 1970s, where he planted a self sustaining eco-system encompassing vines at the heart of the property surrounded by exotic plants and flowerbeds, of which First floor comprises 2 hectares.

There seems to have been a slightly chaotic labelling regime during the 1990s, with Case Basse labels used interchangeably with Intistieti, a vineyard based on poorer soils resulting in wines with greater structure. From 2000 onwards Soldera released his Brunello as only Riserva. In 2006 Gianfranco left the Brunello di Montalcino appellation and moved to labelling Case Basse as Toscana IGT.

Latterly Soldera became associated with a terrible act perpetrated upon Case Basse.

“During the night between 2nd and 3rd December 2012, unknown people broke into Soldera’s cellar at Case Basse; they did not steal a single bottle, but with an extremely serious act of deliberate criminal vandalism for the whole area, they opened the valves of 10 barrels of 6 vintages of future Brunello di Montalcino: 2007-2008-2009-2010-2011-2012. The loss amounted to 62,600 litres of Brunello resulting in considerable economic damage.”

This led him to auction off the remnants of the extraordinary 2010 vintage for children’s charities around the world. In an open letter from the family, he wrote:

“I and my family would like the vintage 2010 to be associated with a very strong and important message that also makes an impact: we would like words and gestures of hope plus, most importantly, tangible help for those less fortunate than us to stem from such a sad and painful episode for my family.

For this reason, we have bottled these remaining 450 litres of the 2010 vintage only in large bottle formats of 3, 5, 6, 9, 12 and 15 litres in size. All these large bottles also have a special and unique hand-drawn label.

We have a certain number of 3 and 5 litre bottles but have also put together (with the very much smaller number of even larger size bottles as detailed above) four super-exclusive complete sets which add up to 50 litres in each set and these will be auctioned/offered as four complete sets in different parts of the world.”

What turned out to be his final act - a defiant demonstration of selflessness in the creation of a charitable legacy – leaves a striking remembrance: a great man as well as a great wine maker.

Looking back to that wonderful dinner held by Vinous Media in London, April 2016, and in homage to one of the greatest ever wine producers, here are the notes from the wines tasted that evening.

The early years

Case Basse 1981

Heady perfumed nose with sweet peppers, then on the palate the freshness of Seville orange with dusted cocoa powder giving the wine a dry, firm edge. Long and insistent.

Case Basse 1982

A nicely developed nose, warm, then sweet lemon peel on the palate with spiced undertones heading into a vibrant, warm finish.

Case Basse 1987

A sensational nose, cloves, oranges and aromatic sandalwood, with a liquor-infused character that in combination with the spiced orange brought to mind crepes suzettes! Very pure with some residual grip.

Case Basse 1988

Very developed nose , with a strong aromatic character (think Myrrh), macerated oranges, a liqueur like texture, and a great breadth of flavours combining fruit and savouriness.

Sleeper vintages

Case Basse 2000 Riserva

A young wine with a soaring complex nose of herb and fruit liqueur, peony and mushroom. Firm palate, structured and focused.

Case Basse 2003 Riserva

Expressive nose, floral, savoury with herbal notes. On the palate the attack is full of black cherries, with hints of cream, and a firm finish with lots of energy and freshness.

Case Basse 2005

Gamey, wild character on the nose with a striking saltiness. The wine is texturally satisfying, with a tight palate of bitter dark fruit and a draft of refreshing redcurrants. Very long.

The mid 1990s

Case Basse 1993 Riserva

Fresh nose with sweet peppers. A huge zingy attack, which is almost too intense. That intensity of cool fruit leads to a dry finish.

Case Basse 1994 Riserva

A pretty aromatic nose is allied to a sense of roundness of the palate. Great intensity, lemony drive, mouth watering and long; so much energy.

Intistieti 1995 Riserva

Huge perfumed nose, peppered and intense. This is a vertical wine of monumental proportions and with an incredibly long finish. A future great.

Case Basse 1995

Darker fruited nose compared with the Intistieti. Fresher too, in a lighter, crystalline style. It’s mouth watering with an insistent finish.

Case Basse 1996 Riserva

Creamy fruit, somewhat muted, palate is fresh and the fruit is once again crystalline, before savoury notes appear on the mouth watering finish.

Reference points

Case Basse 1997 Riserva

A warm inviting nose sign posts a hot year followed by a palate overwhelmingly of black cherry. It’s a direct wine that shows you what it’s got, whilst for now missing out on the complexity of the greatest years, unless of course it's simply masked by youth.

Case Basse 1999 Riserva

A developed, creamy nose serves as a curtain call on a wine that’s structured, powerful, stacked with confit fruit, and an expansive mid palate, ending satisfyingly sweetly.

Case Basse 2001 Riserva

Saline pepper nose, red cherry dominated palate and takes one’s breath away with its energy and verve. WOW!

Case Basse 2004 Riserva

A sweet entry, and gamey resolved attack leads into an intoxicating, heady wine with huge resonance.

The Icons

Case Basse 1983 (en Magnum)

Fresh mature nose followed on the palate by intense, bitter-edged, gorgeous fruit. A wine of intriguing contrasts.

Case Basse 1983 Riserva (en Magnum)

Reserved cool nose. This is very young, structured and elemental. It’s so unevolved and in this regard similar to the Intistieti 2005 Riserva. It makes me wonder if this was in fact Intistieti in disguise.

Case Basse 1990 Riserva

Peppery nose, an energetic attack, deep, with bright fruit and a warm finish. The remarkable complexity of this wine is in its combination of opposites evoking warmth and cold, sweetness and spice.

Case Basse 2006 Riserva

Savoury, slightly meaty nose, a gamey palate, sweet mid palate and a finish that builds in intensity and shows its youthful edge.

Antonio Galloni described Soldera’s wines as having a remarkable ability to age with grace, “a testament to Soldera’s vision, will and obsessive pursuit of quality”. The perfect parting words.

by Wine Owners

Posted on 2018-03-05

We would like to echo the sentiments of Lisa Perotti-Brown – the new face of Bordeaux at The Wine Advocate – who revels in reviewing great wines from vintages less hyped than the universally celebrated ones.

A review of past vintages is so much more pleasurable than one of a current vintage. It can be pursued at leisure, far from the madding crowd of en primeur set-piece campaigns. The wines have been in bottle for some years, and have grown into their skins, allowing them to express themselves and harmonise. There is none of the guesswork required when evaluating young wines. And it is not done as part of a tasting Megathon favouring the most obvious, richest wines…

Here follows a spotlight of vintages which hide truly great wines, many of which still represent good value.

Burgundy 2013

Let's start with 2013, the worst climatic year Burgundy has experienced in a long time, characterized by a dreadful summer of cold, sodden weather. But that’s the thing with Burgundy; its growers refused to give up. They never do. They spent the summer in their Aigle wellies desperately battling the filthy elements and sticky, sucking mud. Coaxing what they could out of their precious vines - their livelihood - trying to make the best of a seemingly bad lot. The coaxing process involved leaf thinning, and sacrificing bunches to give the rest a chance at maturing properly. And that is the thing with Pinot Noir; it responds exceptionally favourably to low yields.

Now, if you like dense, sweet fruit with generous alcohols, 2013 may not be the vintage for you. But if you enjoy intensity of flavour without the weight of a hot year, red Burgundies from 2013 will positively surprise you. All the more so if you first tasted barrel samples back in January 2015; the wines are now positively transformed from that first recalcitrant showing.

It’s well known that a warm, accommodating, crisis-free growing season will result in wines that are generous and velvety-textured in their youth. But these aren’t always the wines that develop into fine, complex maturity. Take 1999 for example, lauded as one of the greatest Burgundy vintages of all time. Indeed, some of the wines are astoundingly good. But just as many others are really quite average. Why is that? Over-generous yields. It’s a fine line with Pinot, between harvesting as much ripe fruit as nature provides and allowing the fecund vine to produce as much as it’s wont.

Back to low-yielding 2013, and the best wines are beautifully crystalline, intense and transparent. Think a cornucopia of red fruits, blackberries and gooseberries: the essential ingredients of a refreshing summer pudding – a balancing mélange of sweet and sharp. Add characteristic Burgundy high notes of salinity (and a mineral-tinged, geological nod-in-the-glass to the inland sea of which the Cote d’Or was once a part) and hopefully you’ve formed a fair mental image of 2013 red Burgundy.

It’s no coincidence that blue chip stalwarts such as Eric Rousseau and Christophe Roumier love their 2013s. Aubert de Villaine sees his Domaine de la Romanée 2013s as long distance runners (in contrast to his more ‘forward’ 2014s). And they are delightful.

2013 is also one of the last sensibly priced vintages before Burgundy prices became vertiginous.

Burgundy 2006

Wines from cooler Burgundy vintages often start out rather awkward, and out of kilter. Their acidity may add definition and length, but can also close the wine down, or conspire with tannins to suppress the essential grape characteristics in a wine.

2006 was one such vintage. Its wines were initially hard to taste, and broadly speaking, unlovely. Many of us viewed 2006 Burgundies as unwelcome magpies in our collector’s nest of more comely vintages.

But now, after a decade in bottle, the wines are starting to show very well. They exhibit well-defined fruit, great length and energy. Next to the 2005s, they may lack heft and powerful tannin structure, but they are nonetheless serious, intense wines. And they are beginning to drink well now. You’ll have to wait at least another decade for your 2005s to come around, but 2006 is a fine emerging vintage that will give pleasure now and for the foreseeable future.

Bordeaux 2011

For Bordeaux, 2011 was always going to be a tough sell. On release, the wines seemed scrawny and mean in comparison with the monumental 2009s and 2010s.

Yet a recent dinner event hosted by Wine Owners showed how dangerous it is to tar a whole vintage with the same presumptive brush, or to judge a more classic vintage too early. The highlights of that tasting were Vieux Chateau Certan 2011 and La Mission Haut-Brion 2011. They were both easily the equal of their counterparts from better-regarded vintages, and represent great value compared with any more recent vintage.

Bordeaux 2006

In Bordeaux, 2006 was a vintage that attracted more than its fair share of negative press, the effects of which are still in evidence today, judging by the affordability of 2006 Bordeaux on the Wine Owners Exchange. The success of a Bordeaux vintage depends on sentiment, and in 2006 combination of negative factors came into play.

First, it came on the heels of stellar 2005. Second, Bob Parker’s favourable rating of the vintage attracted criticism from many pundits, attracting further negative attention. Third, the release prices were too expensive– due at least partly to the high Parker scores. Why else would La Mission Haut-Brion be ready to trade at £1,550 per 12x75cl, yet be overlooked?

[ Top tip: buy La Mission Haut-Brion at this level – half of its opening (mis)price. It is considered a ‘wine of the vintage’, rivalled for this accolade only by the (much more expensive) Mouton. ]

We are fans of the Bordeaux 2006 wines we’ve tasted. They don’t have the powdery tannins and powerful black fruit of the 2005s, but they do have superb energy, and a sappy character that compels you to take the next sip. We see many wines from 2006 as more interesting than their counterparts from 2004 or 2008. Notable examples include Mouton, Pontet-Canet, Leoville Barton, Leoville Las Cases, La Conseillante (just a sampled tip of the iceberg). Whenever tasted comparatively, these showed extremely well alongside relative other vintages.

In our experience, where 2006 performs particularly well is its consistency. Simply put, we’ve never had a poor one. Other low-rated back-vintages produced a number of successes (such as 2007, 2011), but none are as consistent as 2006.

Bordeaux 2002

2002 is another Bordeaux vintage which suffered from poor reputation. The year’s poor weather consigned the vintage to the status of ‘restaurant wine’ before any of the wines were even bottled. But it’s easy to forget that the wines were very well priced; first growths were released at around £800 per case (just one-sixth of their 2015 release prices). If you had invested in 2002 Bordeaux 15 years ago, you would be feeling rather smug right now. 2002 is the vintage for the contrarian that lurks inside every wine enthusiast!

While they were never going to be the most profound expressions of Bordeaux (in the light of the meteorological conditions), the 2002s have consistently tasted savoury, fruity, and sweetly spiced with cloves, cinnamon sticks and liquorice root. At all levels of classification, we’ve yet to stumble across a disappointing example.

Piedmont 2002

In 2002 Piedmont, like Bordeaux, suffered from rotten summer weather. Wine commentators have described 2002 in Piedmont in such terms as ‘wiped out’, ‘disastrous’, ‘severely compromised’, ‘a washout’.

But despite all of this, one wine survived the vintage’s humid gloom (and the hailstorms which repeatedly strafed Barolo) with enough salvaged bunches to benefit from perfect autumnal conditions. This is a wine made with such severe selection that yields were just 12 hl/ ha, and which epitomises viticultural triumph against the odds. The wine in question is, of course, the now-mythical Barolo Riserva Monfortino 2002.

Take a moment to consider the sacrifice involved in making wine with yields as low as 12 hl/ ha. Burgundy considers 25 hl/ ha to be painfully low, and in Bordeaux anything under 40 hl/ha is a very short harvest.

Giovanni Conterno – Roberto Conterno’s late father – called 2002 the greatest Monfortino of his lifetime.

The last word must surely go to Antonio Galloni, whose tasting note and review of this wine encapsulates why it’s so rewarding to seek out the greatest wines within those vintages in the shadows:

“…the 2002 Barolo Riserva Monfortino, a wine that may very well turn into a modern-day legend… 2002 was a cold, rainy year that in many parts of Barolo culminated with violent hailstorms in early September. The weather then turned picture-perfect for the rest of the growing season, but by that time most vineyards were severely damaged. The late-ripening Cascina Francia was an exception. Conterno green-harvested aggressively, which gave the fruit a chance to ripen. …The Conternos were so upset by the poor early press reaction to the vintage they announced they would let no one taste their 2002 Barolo. Conterno has fashioned an old-style, massive Monfortino that pays homage to the great wines of decades past. …It is a deeply-colored, imposing Monfortino loaded with dense dark fruit that today is held in check by a massive wall of tannins…classic, old-style Barolo the likes of which we aren’t likely to see again any time soon. Antonio Galloni, October 2008.

by Wine Owners

Posted on 2015-06-07

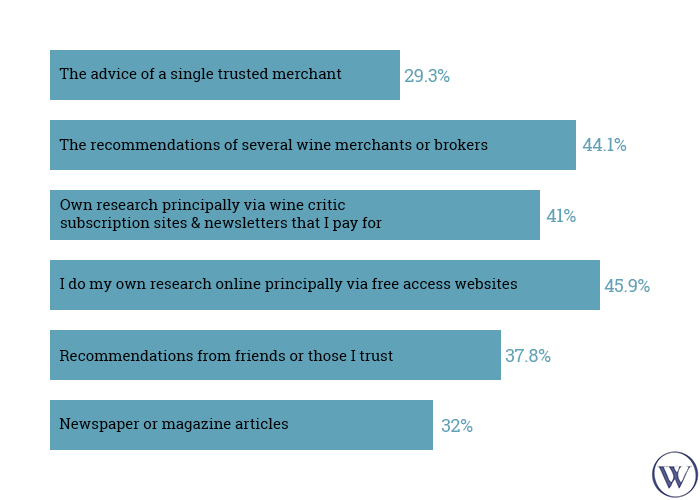

Which wine writers exert the most influence over consumer purchasing decisions of fine wine?

It’s a question we’ve often been asked, and one we wanted to understand in context of what kind of recommendations influence consumers’ fine wine buying decisions.

To find out, we teamed up with Spiral Cellars, and organised a structured research programme through Effective Research. The fine wine purchasing influence ranking is based on 244 questionnaire responses.

We discovered that consumers rely on multiple recommendation sources, and even the least relied-upon source is quite significant in influencing purchases. This also suggests that social media influence is real, and can indirectly contribute towards buying decisions.

There is nonetheless a clear, favorable bias towards online sources, with the subscription sites of leading critics exerting the greatest sway over consumers.

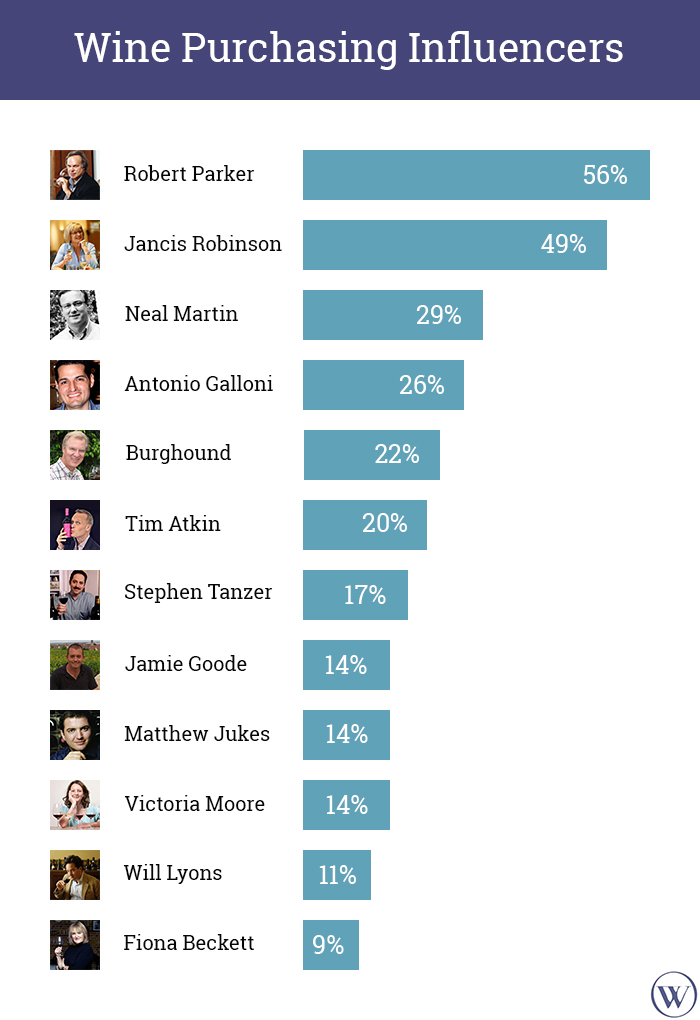

Which critics and bloggers, if any, are you most likely to base a proportion of your buying decisions on?

When it comes to informing a proportion of buying decisions, Robert Parker is the clear winner with more than half of all respondents likely to buy based on his reviews. Neal Martin, his successor for new Bordeaux releases and leading Burgundy critic, is relied upon by 29% of respondents, with Jancis Robinson in a very strong second place position on 49%.

Vinous (Antonio Galloni on 26% and Stephen Tanzer on 17%) showed complementary strength, with Burghound (Allen Meadows) registering 22% and Tim Atkin on 20%.

Whilst consumers have their favourites, their buying decisions will be influenced by a number of critics and writers.

by Wine Owners

Posted on 2015-03-16

With Robert Parker handing over the reins of Bordeaux Primeurs tasting to Neal Martin, what are the implications?

The first, most obvious, change is Neal’s palate.

However objective a critic may be, his or her palate and personal preferences inevitably play a big part. Where Parker excelled was at getting his impressions across in a particularly accessible and descriptive way; not easy when tasting barrel samples. The temptation is to describe a wine in its elemental state elementally, which isn't that interesting to read. He described its future, and over the years demonstrated he was rather good at that.

His personal preferences may have veered towards a sunnier style of wine, but he tended to let the wine buyer know if a wine was stylistically towards one end of the spectrum or another. But it must be very hard to award a great score to a wine that doesn’t move you viscerally, and to that extent personal preferences must come into play.

Martin’s tasting preferences are naturally more European than Parker’s, and is perhaps more likely to be dazzled by finesse and complexity over power, texture and rich fruit. This is a gross oversimplification for sure, but perhaps suffice to say his evaluations will be his own.

The second is winemaking trends.

The trend back towards a more classical form of winemaking is already underway (allied to far better vineyard husbandry than was broadly the case when Parker started out – he is often attributed with raising standards). Use of new oak is being moderated at many Chateaux, and régisseurs are looking at ways to fully express and nuance their amazing terroirs, sub-plots and micro-climates whilst making the most of Bordeaux’s inherent ability to bear and bottle the most age-worthy wines in the world.

The tendency of the late 1980s and 1990s towards making and showing the kind of wines proprietors thought would garner the best scores early on is on the wane. If the world’s leading critics and evaluators of young Bordeaux favour a finer-boned vernacular, this will be reflected in the market, which is more likely than not to reward those styles of wine with the greatest demand.

The third change is context.

Back in the early 1980s there was no Internet, market transparency was therefore limited and the market was much narrower than today’s. Can another critic, however good, assume the same degree of importance and purchasing influence over a market in the way that Parker has achieved? If so, will they come from Europe or do they have to be American? Or Asian?

Will crowdsourcing views and reviews become a proxy for the next leading critic of his or her generation, a perspective that arises with the growing importance of the Internet? I wonder. Some may argue that buyers are too ready in our online age to trust the word of a virtual room-full of complete strangers over the words of an advisor or friend. Whilst such principles may work well for holiday destinations or white goods manufacturers, it’s tougher to see how this will ultimately prevail for the finest of fine wine. How experienced is the taster, do they have a bank of reference points in respect of tasting young wines, and can they draw parallels between what a wine tasted like when in barrel compared with 10-15 years on? Can they recognise the future evolution of a young wine, see similarities and differences, then context (and visualise) the next young wine they taste accordingly? What does it mean when experienced tasters say that great wine is born great? What does great taste like? What’s the palate preference of each taster; where on the spectrum do they sit?

That’s an awful lot of questions to ask of a crowd, especially when most of them have day jobs. Broadly, people may not care about all that of course; but people into their fine wine, and making spending decisions based on the judgement of others, will care. That’s why evaluators of fine wine such as Neal Martin, Jancis Robinson, Stephen Tanzer, Antonio Galloni, Tim Atkin, Will Lyons, and many other talented writers (see here) matter so much.

What could be somewhat significant in turning reputation and influence into market impact is the business model deployed. What I wonder is this: with the Internet capable of coalescing huge audiences and showing the true - often massively underestimated - size of market niches, will blanket subscription firewalls allow wine writers to maximise market influence?

How experts in general monetise their high value content may yet change over the next few years, perhaps in a parallel way that the music business experienced a profound shift from selling records to selling bums on seats and festival tickets. Will the experiential become the bigger money-spinner? How the world’s critics engage with their audience and allow them an element of participation and dialogue may prove decisive for the next Parker, if there is to be one. Being social web savvy can only but help.

The fourth change may be the end to ‘wait and see’.

If the Chateaux knew Robert Parker was coming to Bordeaux, they might hold off from releasing until his scores were known, and the job of negociant and merchant alike was simplified, if sometimes a little delayed.

When Parker didn't come to town within a few months of the new vintage, the market reflected the collective views of the wine industry that had tasted samples most frequently (producers, courtiers, negociants, importers) and added a dose of realism to do with the macro-economic context. Price differentials within a set of wines (e.g. First Growths) were narrower. So, famously, 1990 was priced cheaply in the recession of 1991 as was 2008 in the post-Lehmann, financially sclerotic environment of 2009.

In the short term at least, all the leading critics will turn up to taste on time and publish on time. The extent to which they will collectively or individually influence prices (and demand) remains to be seen, but it would be more surprising if they didn’t have at least some bearing on the market. Producers are more likely to have made up their mind on pricing based on their qualitative assessments early on, and perhaps we shall all be spared interminably long campaigns.

by Wine Owners

Posted on 2014-05-16

What was truly historic about this tasting was that every wine served was from magnum. Since Monfortino was not bottled in magnums every vintage (Roberto's father shied away from larger formats because they had to be hand-bottled) this tasting was of EVERY Monfortino vintage EVER bottled in mags.

The magnums all came from a collector in Italy, known to Roberto, and acquired by Antonio some time ago. Theoretically, because the wines have been stored in exactly the same conditions since release, what you were therefore tasting is the vintage differences, with the exception of the 1970 which was made from bought-in grapes as was the custom of the time. Cascina Francia was bought by Roberto's father in 1974.

The flights were arranged thematically. This was an inspired choice, with warmer vintages grouped together, cooler shades, modern day classics etc.

The magnums were decanted 4 hours in advance of the start of the dinner.

The wines were poured in advance of each course arriving, so that the wines could be tasted alone and with matched dishes.

Flight 1: To Start

Served with crispy chicken thighs and charred lettuce.

1988

Ripe, expressive nose, sweet and pronounced pepperiness. Pale brick rim, limpid ruby core. Really thick glycerol. Grippy and bright, with a persistent citric thread. Mouthwatering finish with tertiary leafy notes.

An hour later a bit loose-knit.

1993

Cool nose. Pure creamy fruit, subdued pepper, orange brick rim with a deeply coloured core. Fresh, intense fruit, orange zesty, progressive cedar notes. A little closed on the mid-palate then blooms into a very long finish.

An hour later rich, confit, firm and excellent.

Wine of the flight.

1995

Sweet nose, elegant, fruity and floral. Pale pink rim with orange tinge. Fluid, integrated palate, crystalline and precise.

An hour later, very complete. Grippy, heady fruit, masculine.

Flight 2: The warm vintages

Served with a layered Foie gras terine, pomegranate, sauternes gel.

1990

Warm pepper nose, powerful and spirity. Translucent rim. So young on the palate, with an amazing entry that is grippy with thrilling acidity. So young.

An hour later less grippy but still super-fresh and exciting. Another decade?

1997

Very overt nose; subtle blueberry notes followed by macerated cherries and summer pudding. Blueberries on the entry, texturally dense with a lifted mid-palate, mouthwatering. Vivid fluid palate and finish. Very expressive yet fine.

An hour later, nose has calmed down beautifully, stunningly layered palate with floral notes. Wine of the flight.

1998

Creamy nose, white pepper, liqueur. Pale orange rim, shining ruby core. Warm entry, a little less precision than the preceding wine, softly spiced fruit, confit aftertaste and a vibrant, fabulously driven finish.

2000

Rye bread nose, spirity, herbal and fresh, with pinot-like undertones. Pink-tinged, strawberry-coloured core. Supremely elegant palate, soft yet dry. Aside from the nose, you would never guess this was the product of warm vintage.

Flight 3: cooler shades

Served with beef Fillet Tataki, pickled onion and something called Wakame.

1987

Rich, heady nose, deep colour, pink tinged rim. Energetic and intense, dramatic yet elegant. Floral mid palate, powerfully and progressively builds to an endless finish. Perfect balance.

Wine of the flight (head)

1996

Not a good bottle sadly. Oxidative Bovril nose, fresh and mouthwatering , sherbet finish, short and un-knit. This was the better of the 2 bottles opened apparently, the first being corked (not served).

2002

Sweet, perfectly poised nose of red and soft fruits. Reminiscent of pinot within the strawberry flavor spectrum. Sweet, gentle pastille fruit. Very long. Beautiful and one for burgundy lovers. Adorable.

Wine of the flight (heart)

2005

Macerated fruit nose. Savoury notes with grippy cool tannins then dark brooding fruit with a sour twist to the mid-palate, before pushing on to an enduringly deep but firm finish.

An hour later, perfectly resolved.

Flight 4: the epic vintages

Served with cannon of lamb and lamb belly, cauliflower pureé and lentils - a masterpiece.

1970

Very alluring savoury nose. Surprisingly deep colour. Slightly gamey, intense and powerful, complex and perfectly poised. Flavours contained by the evident structure of the wine. The wine sings properly with the lamb.

Wine of the flight.

1982

Saline nose, faintly oxidative before it blows off then pure sweet fruit. Slightly volatile, very bright sexy fruit, very intense confit character lifted by a powerful freshness.

1995

Darkly fruited nose, very pure. Translucent scarlet colour. Such a lovely balance. Grainy palate. Elegant, deeply veined fruit.

1999

Primary nose of pure fruit, edgeless. Primary colour with the merest hint of a maturing rim. Stuningly defined, intense but balanced fruit. So refreshing. The ultimate food wine and a future monument for 10-20 years hence.

Future icon of the night.

Flight 5: modern day classics

Served with cheese.

2001

White pepper nose, pure and pale rimmed, limpid ruby, pretty medium weight.

2004

Ripe, fleshy and overtly fruity nose. Deep colour, purple-rimmed. Structured, powerful, grainy palate.

2006

Peppery, fruity, fresh cool nose. Classic form. Very pretty ruby colour. Glycerol drenches the side of the glass. Stunningly pure, linear fruit

Wine of the flight.

by Wine Owners

Posted on 2014-01-06

Worthy of attention on the Exchange this week as a value proposition is the 2010 Coparossa Barbaresco from Bruno Rocca, which outperforms the theoretically superior 2007 vintage but still comes in marginally lower priced (the 2007 appears in the UK market at a low of £211). The Coparossa is effectively a ‘vieilles vignes’ cuvee, sourced from older plantings in First floors of Neive and Treiso, so marks a qualititative step up from the straight Barbaresco bottling, from younger vines, but is not a single vineyard cuvee like the Rabaja. Antonio Galloni and Wine Advocate seem to be in accord that the 2010 Coparossa is the best yet made from a producer who seems to be very much on an upward trajectory in terms of quality and reputation.

According to Galloni, it’s clear from what he has tasted that ‘the best wines from this small, family-run domaine have yet to be made, and that is more than enough to be energised about what is happening here.’ With a constant build in quality, and the fact that in many vintages the Coparossa outscores the single vineyard bottling, the 2010 vintage looks like decidedly good value.

“The 2010 Barbaresco Coparossa brings together the structure of the year with a huge core of fruit, a combination that is hugely appealing. Dark red cherry, plum, cinnamon, licorice and leather all blossom in an expressive, layered wine loaded with personality. With time in the glass, the wine turns explosive. Orange zest, rose petals and cloves linger on the exotic finish. The style is energetic, tense and vibrant.”

95 (1997- 93 pts) Antonio Galloni, Vinous Media

“The 2010 Barbaresco Coparossa is extremely elegant and refined with dried flowers, herbal notes, bright cola and Pinot-like softness. This is a stunning effort. The wine is irresistibly silky and sensuous on the palate, imparting clean fruit flavors that last long on the finish. It delivers fabulous length with seemingly never-ending intensity and persistency.”

Anticipated maturity: 2015-2028.

96 points, Monica Larner, Wine Advocate